An Arboreal Studies Network, Lecture Series and Creative Exhibition

-

It’s all about connecting lines – from lines on a page of literature to the bark of a tree. This project proposes new ways of understanding and appreciating trees through literature. It examines forms of tree writing or arboreal imaginaries in Irish literature and beyond. LIT began life as an Irish Research Council New Foundations project (in partnership with Crann: Trees for Ireland). The project outcomes included the formation of a research network; a public lecture series “Literary Lives of Trees”; and a digital exhibition “Tree and Tell” featuring submissions from the general public. LIT continues to advocate for tree culture anew and to generate knowledge about Ireland’s interconnected tree and literary cultures.

-

Literature provides a way of not only imagining trees but thinking with them too. The literary imagination can prompt us to consider what trees mean to us, and how we might recognise their rights. When writers come to include a tree in their literary text, they may be doing more than simply providing some green and brown texture. They may be thinking with and about a more-than-human arboreal world.

-

Timothy Ryan Day teaches Shakespeare, ecocriticism, and writing at Saint Louis University’s Madrid Campus. He is the author of the monograph Shakespeare and the Evolution of the Human Umwelt: Adapt, Interpret, Mutate (Routledge 2021), the novel Big Sky (Adelaide Books 2020), and the poetry collection Green & Grey (Lemon Street Press 2018). His articles and translations have appeared in Green Letters, and Ecozone. His research interests include Shakespeare, Narrative Scholarship, and Biosemiotics.

Katie Holten (Dublin, 1975) is a visual artist and environmental activist. She has created Tree Alphabets for New York City and Ireland. In 2015 she published the book About Trees. Holten represented Ireland at the 50th Venice Biennale. Her work has been exhibited in museums internationally, including solo exhibitions at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, New Orleans Museum of Art, Bronx Museum, Nevada Museum of Art, and Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane. Her book The Language of Trees is out now.

Stephen O’Neill is Associate Professor in Shakespeare Studies at Maynooth University, with research interests in contemporary intersectional Shakespeares and arboreal humanities. The author of Shakespeare and YouTube (Arden Shakespeare / Bloomsbury, 2014), Staging Ireland: Representations in Shakespeare and Renaissance Drama (Four Courts, 2007), and editor of Broadcast Your Shakespeare (Arden Shakespeare / Bloomsbury, 2018), he has published widely on adapted Shakespeare. Recent work includes articles on HBO’s Westworld in Cahiers Elisabethains and Maggie O’Farrell’s award-winning novel Hamnet in Shakespeare. With Diana Henderson, he co-edited the Arden Research Handbook to Shakespeare and Adaptation (Arden Shakespeare / Bloomsbury, 2022) and, with Ton Hoenselaars, Shakespeare and Refugees (Routledge, 2021).

Anna Pilz is Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow in the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures at the University of Edinburgh (2020–22). To date, she has published in the field of Irish Studies, with a particular specialism in women’s writing, cultural and literary history, as well as on the intersection between literature and environmental history. She is co-author of 'Trees, Big House Cultures, and the Irish Literary Revival' (New Hibernia Review, 2015) and has a chapter on 'Narratives of Arboreal Landscapes' in Malcolm Sen's A History of Irish Literature and the Environment (Cambridge UP, 2022). Her first monograph on narratives of trees and woodlands in Irish writing is contracted by Liverpool University Press.

Keith Pluymers is an Assistant Professor of History at Illinois State University where he works on early modern environmental history. Prior to joining ISU, he completed his BA at the University of Delaware, his PhD at the University of Southern California, and a postdoc at Caltech. His first book, No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (University of Pennsylvania Press) was published in 2021.

-

Stephen O’Neill asks “What's your favourite reference to trees in Irish literature?”, on RTE Brainstorm. The article surveys examples of trees in Irish literature, with the aim of seeking the public’s input to build an archive of literary references to trees.

-

Chapter proposals are invited for a book, Tree Lines: Arboreal Agency in the Creative Arts.

The book aims to build on current research on trees in literature and culture by asking how we can identify and represent trees in non-anthropocentric and non-anthropomorphizing ways. The book’s title is intended to convey lines of bark, thus gesturing towards tree life, as well as the lines of a text, a painting, or the frames on a screen through which we render that life. How do we move towards a language of trees? What critical paradigms and creative responses might now be called for to realize a greater apprehension of arboreal life and alterity? Drawing together such fields as eco-criticism, film, creative practice, history, geography, and critical plant studies, this collection will examine a broad set of representations and understandings of arboreal lives across historical periods to arrive at critical, creative, and ethical approaches to arboreal ontologies and temporalities.

Further information here.

Tree and Tell

a digital exhibition

About

In 2022, Literature and Ireland’s Trees (LIT) invited the public to submit their favourite tree in Irish writing. The call was publicized on the project website, RTE Radio, and RTE Brainstorm. The aim was to build a broader understanding of the role of trees in our literary culture, and to record how literature helps us to regard trees as life-forms deserving our respect and protection.

What follows are a selection of the submissions received from members of the public. The examples come from Irish literature and culture, with the exception of the Joyce Kilmer quote.

Thanks to all those who shared their memorable literary tree.

Dr Stephen O’Neill, Project Leader

"The willows sign and sway and sing about love but you don’t need ears to hear the trees, you only need to listen" (Lynne Buckle, What Willow Says, 2022)

〰️

"The willows sign and sway and sing about love but you don’t need ears to hear the trees, you only need to listen" (Lynne Buckle, What Willow Says, 2022) 〰️

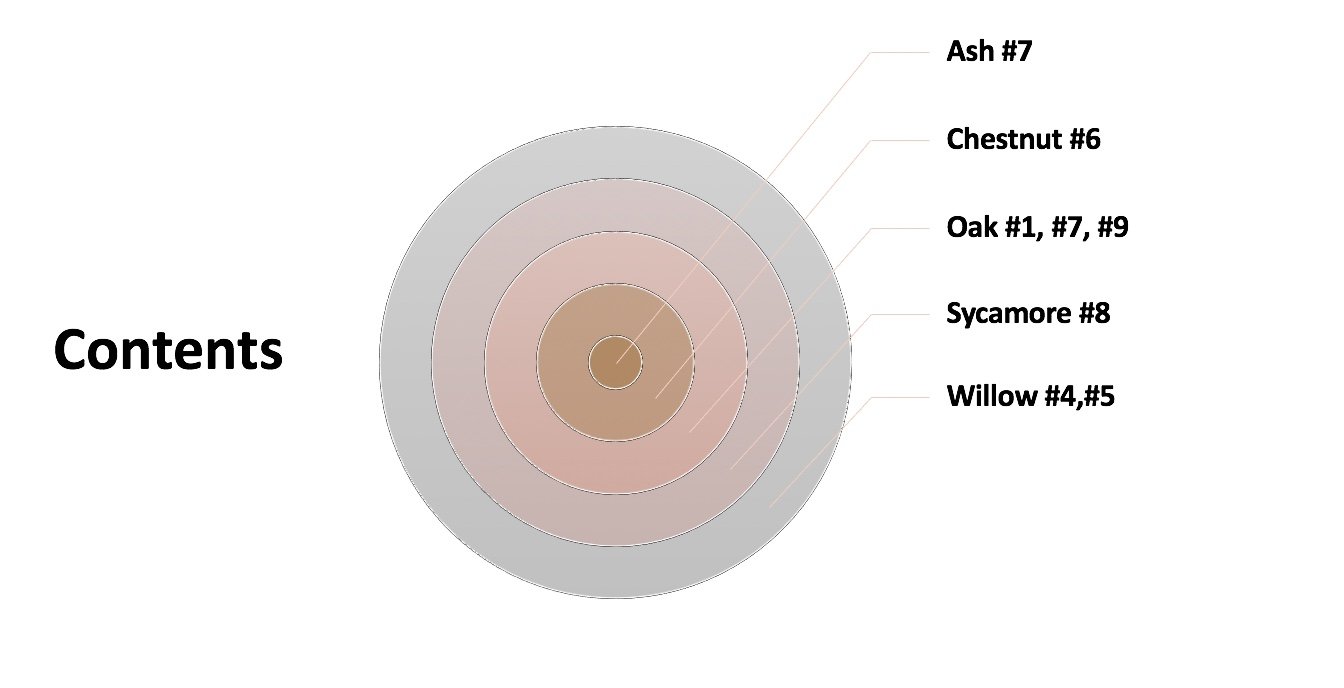

#1 Tree and Tell

My arms are round you, and I lean

Against you, while the lark

Sings over us, and golden lights, and green

Shadows are on your bark.

— J.M. Synge, ‘To the Oaks of Glencree’ (1911).

Tell: “One of my favourite references to trees is J.M. Synge’s poem, ‘To the Oaks of Glencree’. Given his untimely passing and long standing ill-health, it has always felt to me especially sad.”

Submitted by: Siobhan Purcell.

#4 Tree and Tell

A country road. A tree. Evening. Estragon, sitting on a low mound, is trying to take off his boot. He pulls at it with both hands, panting. He gives up, exhausted, rests, tries again. As before. Enter Vladimir.

—Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot (1953).

Tell: “The willow tree in Waiting for Godot. It symbolises hope for me in that in the second act leaves appear on a supposedly dead tree, suggesting change and renewal in the midst of death and decay.”

Submitted by: Declan Owens, Co. Down.

#6 Tree and Tell

I thought of walking round and round a space

Utterly empty, utterly a source

Where the decked chestnut tree had lost its place

In our front hedge above the wallflowers.

—Seamus Heaney, ‘Clearances’ (1990)

Tell:

“In but four lines, I feel Heaney perfectly captures the confusion that characterises the in-between stages of our lives. The shock that something years in the making can be lost overnight, like the chestnut.”

Submitted by: Katie Guiry, Co. Waterford.

#2 Tree and Tell

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

—Joyce Kilmer, ‘Trees’ (1914).

Tell: “Learnt at school aged 8 years and always remembered ... Love this poem and what it says about our beautiful trees".

Submitted by: Bereneice O’Rourke.

#5Tree and Tell

Leafy-with-love banks and the green waters of the canal

Pouring redemption for me, that I do

The will of God, wallow in the habitual, the banal

Grow with nature again as before I grew.

—Patrick Kavanagh, ‘Canal Bank Walk’(1958).

Tell: “My selection relates to the trees lining the canal banks; willow and poplar are most frequently seen. As well as a tree lover, I am a horsewoman, and canals were built for working horses. A horse could pull far more goods loaded into a barge or narrowboat than it could on a cart, as the water bore the weight. Horses and their owners worked the canal routes in all weathers and seasons. The trees provided shelter and shade. They also provided a small amount of food, firewood and goods such as willow for basket making. Willow and poplar host great biodiversity, from shield bugs to bird nesting sites, and the shade they cast prevents the water from getting too warm for fish and amphibians. The line of the canal can often be spotted from the attendant line of trees across the landscape. I enjoy visiting canals, and taking narrowboat trips where possible.”

Submitted by: Clare O’Beara, Co. Dublin.

#7 Tree and Tell

All the birds in the forest they bitterly weep

Saying, ‘Where shall we shelter, where shall we sleep?’

For the Oak and the Ash, they are all cutten down

And the walls of Bonny Portmore are all down to the ground”.

— Loreena McKennitt, Bonny Portmore (1991).

Tell: “Your project, ‘Literature and Ireland’s Trees”, is so heartening. I am always eager to read more about trees, in both non-fiction and novels, poetry, and myth, but when I search for new books, they are too often about England—not that many of those aren’t wonderful. I would love to find more about Ireland’s and North America’s trees. I am from the United States, and only have one grandparent of Irish heritage. His son, my father, gave me my love for literature and trees. I’m sure you’ve included Diana Beresford-Kroeger’s books in your list. To Speak for the Trees is an obvious choice, but have you added The Global Forest? In the chapter “Sacred Trees” she mentions Kildare. My favorite chapter is “The Paranormal: The Trees and the Forests of the World Exist in God.” It is about a farming couple in eastern Canada, but it evokes Ireland in a mystical experience within a circle of trees. In “Fite Fuaite: An Teanga is an Tí” Siobhan de Paor states that “Ireland is the most densely named country in Europe. It is also one of the most sparsely populated. This suggest that our ancestors were intimate with their environment. That they esteemed nature to the degree that every rock, stream and field, was worthy of a name….This view of Nature as a sentient nurturer, as a Mother, is stored in the Irish Language.” She also mentions oak trees. Naming places in nature is also important to Native people in North America. The popularity of Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants is encouraging. She is a botanist and an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. I am often struck by the similarities in history, and of beliefs of these people and of the Irish. Neither culture suffered from plant blindness, as so many people today do. So, more power to you in your quest. I think that many will be grateful for what you are doing. ‘Plant native trees and save the old ones’.”

Submitted by: Carol Diamond, North Carolina.

"an chaoimhsgeach dob easdadh d’eón" | "precious thorn tree, storehouse for the birds" (Laoiseach Mac an Bhaird, 'Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall' | 'The Felling of a Sacred Tree' (early 17th century).

〰️

"an chaoimhsgeach dob easdadh d’eón" | "precious thorn tree, storehouse for the birds" (Laoiseach Mac an Bhaird, 'Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall' | 'The Felling of a Sacred Tree' (early 17th century). 〰️

#8 Tree and Tell

It was a kindly tree. When the children toppled, the sycamore's network of branches broke the fall for little limbs and let them down lightly. No bone was ever broken.

—Joseph Brady, The Big Sycamore (1958).

Tell: “In my pre-teen years I read ‘The Big Sycamore’ by Joseph Brady which was published in 1958. It tells the story of the Brown family and their home in Grangemockler, South Tipperary. Although fictional, it is generally accepted that the family was the actual Brown family which included Cardinal Brown and our renowned poet Maire Mac an tSaoi. The whole story is typical of its time, full of the healthy joys of rural life. It is multi-layered and has many themes. However, what makes it relevant to your research is that throughout the book the childhood nostalgia is symbolised by the big sycamore tree that grew in the front garden of the family home.”

Submitted by: John Lawless, Co. Waterford.

Acknowledgements:

In creating this exhibition, Stephen O’Neill would like to thank IRC New Foundations scheme; Maynooth University Department of English; Katie Holten; Katie Guiry, Maynooth University SPUR programme; and Jim Carroll, RTE Brainstorm.

#10 Tree and Tell

listening up for a long moment, lost in what creaks and sways the tops like bell ropes.

— Mark Granier, Breathing Space, Knocksink (2022).

Tell: “I am working on a sequence of short essays and poems (kindly funded by The Arts Council), Notes On Woods, that gathers my own feelings about/experiences with woods and trees, from ubiquitous plantations to particular trees, or particular places, such as the mature pine woods in Knocksink, Enniskerry”.

Submitted by: Mark Granier, Co. Wicklow.

#3 Tree and Tell

For the house of the planter Is known by the trees.

—Austin Clarke, ‘The Planter’s Daughter’ (1929).

Tell :“Not a specific tree but I always think of the line from Austin Clarke's poem the Planter's Daughter when I'm out and roaming around fields... The house of the Planter is known by its trees... It says so much about Ireland's entwined political and ecological history and it is still true today".

Submitted by: Eimear McNally, Co. Louth.

#9 Tree and Tell

He unscrewed the bottom to allow it fall out, tapping the end until an ancient pen appeared from within; a beautiful one-piece, silver dip pen elaborately carved, with sprawling oak branches hiding secrets known only to O'Conor Kings.

—Mario Corrigan, The Battle for Coman’s Wood (2015).

Tell: “I loved the idea of bringing old Irish stories' to life in a modern environment and wrote a children's book with four or five classes through 3 schools in Roscommon - I called it ‘The Battle for Coman's Wood’ and later when two schools combined, they named the new school Coman's Wood - at the centre of the wood and the story lay a giant oak - maybe being from Kildare Town the oak had always called to me - Brigid's tree - a tree of power and majesty.”

Submitted by: Mario Corrigan, Co. Kildare.

An Arboreal Education in Lynn Buckle’s What Willow Says (2021)

by Katie Guiry

“She asks me what the tree thinks of the state it is living in. ‘It doesn’t.’ how do you know?”

From the moment she first learnt to read lips, Grandchild was swaddled in tales of princely herons, mother goddesses and water kelpies, leaving her with an endless imagination. Such is the more-than-human story conjured by Lynn Buckle in What Willow Says (2021), a novella which has certainly earned its place among other arboreally-themed works, such as Richard Powers’ The Overstory (2018) and Elif Shafak’s The Island of Missing Trees (2022). Through constructing the narrative around a deaf child, Buckle invites us to consider the young character’s unlikely perspective on all things arboreal. She is untouched by the colloquial objectification of trees, that, Buckle may be implying, literature has played a part in. As her novel breaks from this tradition, recognising the trees’ aliveness, in addition to their ability to speak; albeit in a manner alien to most. Grandchild embodies these ideas, insisting that Grandmother learn not just ISL – “you should know sign language” – but the language in which the trees are fluent – “listen tell me what it says” (p.68/p.15). For their predicament mirrors her own, inspiring an empathy within. It is this compassion which sets Grandmother’s arboreal paideusis in motion, the driving force of the novella.

Grandmother is not unfamiliar with trees. They act as her muse, inspiring not only her art, but her stories. Yet, her ignorance is laid bare as early as the opening line – “We struggle to hear in our household”, an observation that applies not only to Grandchild, but Grandmother also, who, despite her connection to nature, fails to truly acknowledge their presence: – “All those years studying their structures, weights and textures while missing their inherent languages” (p.1/p.13). Resultingly, her initial attempts to understand them are as fruitless as her attempts at ISL. Whether it be hands or branches, people or trees, she is outside comprehension. However, as the novel progresses, she comes to realise that there is something of people in plants, and of plants in people. That the histories “stored within [the] scarred bark and wounded limbs” of a tree, are not unlike the “folded character [within] hands” (p.79/p.83). Lines, dents and bumps prove universal storytellers. There is so much to be said in the movement of living things, the swaying of branches cognate to the signs of hands. Thus, although rudimentary, her knowledge of ISL allows for her integration into the conversations of the woods, with the trees’ speech echoing that of her Granddaughter’s.

Buckle’s handling of familial love and loss is as striking as it is gentle. Bordering on the poetic, the writing softens each heavy blow effortlessly, capturing the hearts of its readers in but 116 pages. However, what is so often overlooked is the novel’s arboreal theme. For, in dealing with the different forms language can take, Buckle invites us to not just hear, but listen to the world around us. Her expert harnessing of the power of the literary imagination encourages a greater comprehension of nature overall, as seen through the chapter subtitles that convey weather and geolocation. In this way, the novel is unconventional, for it is less of a direct commentary on our relationship with trees, but an experience, through which the reader can draw their own conclusions alongside that of the characters.

Katie Guiry is a student at Maynooth University and a researcher on LIT project as part of Maynooth University Summer Programme for Undergraduate Research (SPUR). This programme is unique to Maynooth University, offering select undergraduate students an insight into the field of research, under the mentorship of a faculty member).

#202🌳

Tell us about your favourite tree in Irish writing!

What would you want that tree to say now?

-

in conversation with Lynn Buckle, author of What Willow Says”.

Lynn Buckle’s second novel, What Willow Says, was published by époque press and won the international Barbellion Prize. It is a celebration of nature, deafness, and communication through the unique language of trees. Other publications include The Groundsmen, What Meets the Eye; The Deaf Perspective, Imagining the City, Infinite Possibilities, Brigid, and literary articles for The Irish Times, Books Ireland Magazine, etc. She was awarded a John Hewitt Society Bursary, Greywood Arts Carers Residency, shortlisted for Red Line Short Story Competition, and represented Ireland as a UNESCO City of Literature Writer in Residence 2021 at the UK National Centre for Writing. She judges several writing competitions and hosts the Irish Climate Writers at The Irish Writers’ Centre, where she interviews authors, NGOs, and politicians on climate action, encouraging writers of all genres to include positive climate solutions in their fiction.

-

Public Lecture

Monday 5 September 2022 via Zoom

Public Lecture

Monday 13 June , 7pm, via Zoom

-

in conversation with Dr Anna PIlz and Dr Brandon Yen

-

Our speakers will talk about their research on Ireland’s interconnected literary and arboreal cultures, and consider approaches to the tree in writing and painting.

-